“PDA or Demand Avoidance in Autism? Understanding the Difference”

- taniaslt

- Sep 24

- 4 min read

Updated: Oct 7

Navigating the world of autism can be challenging, particularly when it comes to understanding behaviours like Pathological Demand Avoidance (PDA) and autistic demand avoidance. Confusion often arises because both involve a resistance to demands. However, the reasons behind this resistance are quite different. This post aims to clarify these differences, explore their similarities, and equip caregivers with practical strategies to support individuals exhibiting these behaviours.

What is Pathological Demand Avoidance (PDA)?

Pathological Demand Avoidance is a profile closely associated with autism, distinguished by its unique characteristics. Individuals with PDA show an extreme avoidance of everyday demands, impacting their day-to-day life significantly. This avoidance isn't merely a choice; it's frequently rooted in anxiety and an urgent need for control over their environment.

PDA can exhibit itself in various forms, such as:

Evasion of demands: For example, a child might refuse to complete homework or chores, even if they are straightforward and reasonable.

Social manipulation: An individual might divert attention away from what is requested by initiating unrelated topics or even employing humour to deflect focus.

Emotional outbursts: A teenager might experience a meltdown when faced with completing a simple task like getting dressed, overwhelmed by the pressure.

Recognising PDA emphasizes understanding that avoidance typically arises from being overwhelmed, not simply from defiance.

What is Autistic Demand Avoidance?

Autistic demand avoidance encompasses a broader range of behaviours seen in many on the autism spectrum. Though it shares some characteristics with PDA, it's often not fuelled by the same level of anxiety-driven escape. Instead, this type of avoidance may result from sensory overload, difficulty with making transitions, or challenges in grasping social expectations.

Typical features of autistic demand avoidance include:

Resistance to change: For instance, a child may struggle if their usual route to school has been altered unexpectedly.

Sensory sensitivities: An individual might refuse to participate in activities that involve loud noises or bright lights due to overwhelming sensory input.

Communication challenges: A child may find it difficult to express their discomfort with specific requests, resulting in a withdrawal or refusal.

While both PDA and autistic demand avoidance present as resistance, the triggers and motivations can vary widely.

Overlapping Characteristics

Although PDA and autistic demand avoidance differ, they share common traits. Both can lead to significant challenges in social situations and daily life. For example, individuals within both categories might face anxiety when confronted with demands, which can prompt avoidance behaviours.

Furthermore, both profiles may show:

Difficulty with authority: Whether it’s a parent, teacher, or caregiver, some individuals may demonstrate a strong resistance to guidance, preferring to make independent choices.

Emotional dysregulation: Both groups may have a hard time managing their feelings, resulting in extreme reactions or a desire to withdraw from social settings.

Understanding these overlaps is vital for caregivers and educators to develop more effective support strategies tailored to individual needs.

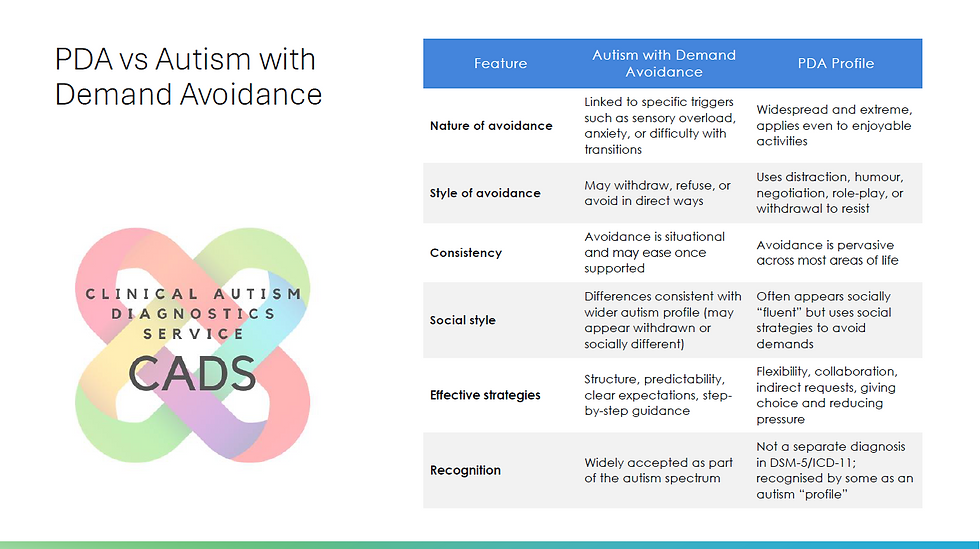

Below are some key distinctions that are often highlighted in clinical and research discussions:

1. Underlying Framework

Autism with demand avoidance: Demand avoidance is understood as one of many possible autistic traits. It often arises due to difficulties with flexibility, sensory sensitivities, heightened anxiety, or difficulties processing demands.

PDA profile: PDA is described as a distinct profile within the autism spectrum. It is characterised by a pervasive and extreme avoidance of everyday demands, often driven by an anxiety-based need for control.

2. Nature of Avoidance

Autism with demand avoidance: Avoidance may look more situational (e.g., avoiding certain school tasks, avoiding noisy environments) and linked directly to sensory, social, or cognitive challenges.

PDA profile: Avoidance tends to be more global and extends across everyday routines and expectations, even those the individual would usually enjoy. Strategies can include distraction, negotiation, withdrawal, or more overt resistance.

3. Flexibility and Social Style

Autism with demand avoidance: Social interaction differences are usually consistent with the broader autism profile (e.g., differences in reciprocity, difficulties with peer relationships).

PDA profile: Children and adults often present with a more socially fluid style, using charm, role-play, humour, or distraction to avoid demands. This can make their challenges less visible or misunderstood.

4. Response to Support

Autism with demand avoidance: Strategies such as structured routines, clear expectations, and step-by-step support are often effective.

PDA profile: Standard autism strategies may heighten anxiety and resistance. Approaches that focus on collaboration, low-demand environments, choice, and indirect communication tend to be more successful.

5. Recognition and Controversy

Autism with demand avoidance: Well recognised in both clinical and educational settings as a common autistic feature.

PDA profile: Remains controversial. PDA is not a separate diagnosis in DSM-5 or ICD-11. Some clinicians recognise it as a meaningful profile of autism; others see extreme demand avoidance as part of broader autistic presentations or linked to anxiety.

In summary:

All individuals with PDA are considered autistic, but not all autistic individuals with demand avoidance have PDA.

The distinction lies in the pervasiveness, intensity, and style of avoidance, as well as the types of support that are most effective.

Final Thoughts

Grasping the differences between Pathological Demand Avoidance and autistic demand avoidance is vital for providing effective support to individuals on the autism spectrum. While both concepts involve resistance to demands, their motivations and expressions can differ significantly. By identifying these distinctions and applying tailored strategies, caregivers and educators can foster an environment that encourages understanding and personal growth.

As knowledge of these behaviours expands, approaching each individual with empathy and adaptability is essential. With the right support, those facing PDA and autistic demand avoidance can flourish and navigate their unique challenges successfully.

Comments